Philosophy is a 3000 year long conversation, and since coming into a conversation halfway through is generally a recipe for confusion, we begin with the man who largely started the conversation: Socrates.

Socrates and Plato lived in the 300’s BC in Athens. Socrates wrote nothing; Plato wrote prodigiously. Plato was Socrates student; Aristotle was Plato’s student. These 3 men are the intellectual foundation of the Western world.

The Republic is a huge book and entire college courses are taught on it, but hopefully this gives you a taste of Plato’s writing and ideas.

About The Republic

The Republic opens with “cast of characters” as though you’re about to read a play. Wait a minute! Isn’t this a work on philosophy? Isn’t this about high-minded ideas? Well, yes, it is. But the form in which the ideas are expressed is a play, a “dialogue”. You’re reading a script, albeit one not intended for actual performance.

Why a play? Because it’s safer. You can say things in a play that are potentially dangerous, but if called on it, “well, it’s just a play.” And ideas are dangerous, both in ancient Athens and today. Because ideas have consequences. If you truly believe something to be true, you will act on it. (We modern, Western Christians might take this to heart.) When ideas cause actions that threaten the powerful, they try to squash those ideas. Cancel culture isn’t new, and Plato’s dialogue opens with a story of one of the first Westerners ever cancelled for his ideas: Socrates.

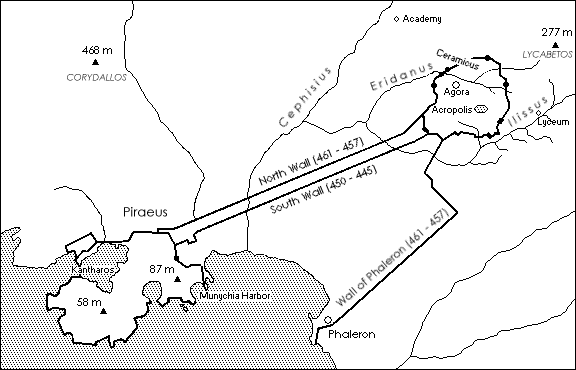

I went down yesterday to the Piraeus with Glaucon the son of Ariston, that I might offer up my prayers to the goddess; and also because I wanted to see in what manner they would celebrate the festival, which was a new thing. I was delighted with the procession of the inhabitants; but that of the Thracians was equally, if not more, beautiful.

One of the key questions of the Republic, “what is justice”, is immediately illustrated here, but only if you understand the setting. By the time this is written, Socrates is dead: convicted and executed by the great Athenian democracy for what amounts to blasphemy or subversion. Specifically, Socrates crime was “promoting false Gods.” He paid for it with hemlock tea.

Plato is defending his teacher here, pointing out that “a new festival” to a new goddess (from rival city-state Thrace) was already going on while Socrates was alive. Socrates didn’t bring the false gods; they were already here. We think of the “Greek Gods” as a group, but each city state jealously guarded its own: Athena was the leading goddess of Athens (obviously) and Thrace worshipped the goddess Artemis. It is likely an Artemis statue that is being brought into the port of Piraeus here and the cause of “the festival” to worship the new goddess.

What is Justice?

The recurring theme of The Republic is how to have a just society. Plato isn’t a populist, but this is his “golden escalator ride”, and he starts with a bang: accusing the Athenians of murder for executing Socrates unjustly. The remainder of the book will cover questions like: “what is justice?”, “how to be a good person?”, “how to raise the young to be good citizens?”, “what are the skills of a good ruler?”, “what is the soul?”

The overarching theme is the separation of power and knowledge — how to have justice even when ignorant people are in charge (a question of no utility in our republic, which is led by brilliant scholars, of course.) How to use reason with people who refuse to be reasonable or to listen? (Again, no applicability today at all.)

(Dr. Michael Sugrue passed away earlier this year, but spent his entire Princeton career promoting Western civilization and literature despite the growing unpopularity of both. This video is from 1992 but it remains the single best summary of Plato’s “what is justice” debate, so it’s well worth 40 minutes of your time. I’ll be using both Daniel Bonevac and Michael Sugrue regularly in this series.)

We tend to think of justice as having to do with law or fairness, but Plato’s definition is much broader. For Plato, justice can be thought of almost the way we think of ethics, as an answer to the question, “what is the correct way to live?”

The various definitions of justice that are brought up in this conversation seem circular.

Justice is being honest (Cephalus)

Justice is giving each person his due (Polemarchus)

Justice is benefiting your friends and harming your enemies (Polemarchus)

Justice is benefiting good friends and harming bad enemies (Polemarchus)

These just shift the definitional problem, since now instead of defining “justice”, we must define “honest” or “good”. Defining “good” is one of the foundational problems of moral reasoning all the way through today, so this isn’t really that helpful.

Justice is the interest of the stronger (Thrasymachus)

This definition is what we would call “might makes right”. But it’s not satisfying either. If justice is a virtue (and Plato insists that it is) then it ought to be universally applicable. Thrasymachus definition of justice being the will of the powerful strips that away.

This video ends when Socrates and his companions decide to “create a city in speech”, hence this dialogue’s name: The Republic. Since looking into a human soul is impossible (unless you’re George W. Bush talking to Vladimir Putin apparently), they will use the presence of justice in that fictional city to infer justice within the human soul. And what a city they produce! This is the central 5-6 books of The Republic and while they’re well worth your time, not everyone is that motivated, so I’ll be including excerpts in the readings below and the next class.

Rings of Invisibility

One of the reasons to read Plato is his metaphors. These are reused frequently even by people who don’t know their source. Ever heard of “the ship of state” — Plato. One metaphor has to do with justice directly, the Ring of Gyges. Oh, you thought Tolkien invented the ring of invisibility? Plato.

Could you resist the ring? More broadly, could such a ring ever be used justly? By anyone? Tolkien’s answer is “no”; that’s the whole point of LOTR. In Tolkien’s tale, overcoming the temptation of the evil ring requires either childlike innocence (the Hobbits) or divine courage (Galadriel).

Tolkien is a modern Christian with a view of man as a fallen and sinful creature though. Socrates and Plato don’t share this view of man — they’re pre-Christian pagans. For the ancients, man is potentially perfectible (moderns like Mill and Hume and Nietzsche agree). Plato is explicit about this in his discussion of the soul (more on that next week). In a long-winded response to Glaucon’s Ring of Gyges reference, Socrates argues that since justice in the soul is intrinsically valuable (not because it results in good things, but it is a good thing itself) someone strong enough (the kind of man Plato would crown as a philosopher-king) might well be able to use the ring for good.

“What if there are no gods?”

After Socrates dispatches Thrasymachus and his “might makes right” argument comes what I think is one of the most fascinating exchanges in the Republic. Glaucon and Adeimantus argue that a strict definition of justice doesn’t matter. What matters is how we ought to live, and they argue it’s better for the individual to live unjustly (for his own gain) than to bother trying to deal fairly or pay his debts or be honest, etc…

With a view to concealment we will establish secret brotherhoods and political clubs. … I shall make unlawful gains and not be punished. Still I hear a voice saying that the gods cannot be deceived, neither can they be compelled. But what if there are no gods? or, suppose them to have no care of human things --why in either case should we mind about concealment?

By his “what if there are no gods” question, Adeimantus gets to the key moral reasoning problem of atheism, a problem has bedeviled (pun intended) all modernist philosophers: how to define a universal moral code (a definition of “right” and “wrong”) without a divine source. If the only thing constraining my actions is temporal punishment, why not get away with whatever I can? All the modernists (starting roughly with Francis Bacon) have struggled with this, and when we get to Bacon and Descartes we’ll talk more about it. Adeimantus words foreshadow what will become a huge problem though. How huge? Steven Pinker, the great evolutionary psychologist at Harvard and one of the smartest atheists alive, has spent much of his career trying to solve the moral reasoning problem. You can judge whether he’s succeeded if you like:

The answer to this article is literally on page 1 of Plato’s Republic:

Polemarchus said to me: “I perceive, Socrates, that you and our companion are already on your way to the city.”

“You are not far wrong,” I said.

”But do you see”, he rejoined, “how many we are?”

”Of course.”

”And are you stronger than all these? For if not, you will remain where you are.”“May there not be the alternative,” I said, “that we may persuade you to let us go?”

“But can you persuade us, if we refuse to listen to you?” he said.

“Certainly not,” replied Glaucon.

“Then we are not going to listen; of that you may be assured.”

Reason is a great tool for those who choose to be reasonable. But what to do with those who refuse to be: “can you persuade us, if we refuse to listen to you?”

Conclusion

One of the most frustrating things about The Republic is that Socrates never actually gives his own definition of justice. Thrasymachus harasses him and Glaucon pleads with him but all in vain. However, in all his dodging and weaving, a few themes do become apparent:

Harmony - The just society is one that the pieces work well together. If there is friction, it’s a sign of injustice.

Specialization - A just society fits people into roles that match their abilities and desires. For Socrates, this isn’t about freedom or rights in the Enlightenment-liberal sense but about efficiency. It’s good for the city if each individual citizen focuses on things he’s good at.

Good for the Soul - We’ll talk more about Plato’s view of the soul in the next article, but justice is the highest virtue for Plato (and for Aristotle) so it must inexorably be rooted in goodness. If this seems like a circular definition to us, we should ask ourselves why it wasn’t a circular definition to Plato. Maybe we’re WEIRD.

Why does Socrates refuse to give his own definition of justice? Because these aren’t simple questions with simple answers. Philosophy isn’t something you can memorize the answers and take the test. Asking a question like “is it just” inevitably touches on questions of goodness, responsibility, and virtue, even the basic question of “what is man?” A simple answer to that question is the domain of the gods, far above Plato’s pay grade, and thus he doesn’t place one in Socrates’ mouth.

I came upon this mosaic on the porch of a house in Pompeii when I was 27 years old. It’s famous, but I hadn’t heard of it beforehand (thanks for that second-rate education, UC Irvine.) Over about 5 minutes of looking at it, this mosaic profoundly altered my selse of connection with the ancient world. To this day, it remains my favorite example of the ancients being “just like us”. If you can’t tell from the context, “cave canem” is Latin for “beware of dog”. (And no, UC Irvine didn’t require Latin; I took it in high school for fun.)

Ancient people (whether Babylonians or Greeks or Mayans or Mongolians) viewed the world radically differently than you do, but they had your intellect, your drives, your fears, your passions. The line between good and evil ran through the center of their hearts1 just as it does through the center of yours. You have fancier toys, but inside, not much has changed.

That’s why Plato’s worth reading. Because the most important questions are timeless.

Readings

Review Questions

Why did Plato write in dialogues? What's the benefit of wrapping his argument in a story?

Fortunately, we modern, industrialized, Westerners don't execute people for heresy anymore. Or do we? Is there a modern (albeit lass drastic) parallel to how Socrates was treated?

Summarize Thrasymachus argument that “might makes right”. How would you argue against him?

Why does atheism present a problem for establishing a universal moral code? Can you define “justice” without defining “good”? Can you define “good” without God? (Note: you won’t have a rock solid answer here. We’ll be returning to this regularly over this course.)

How well does modern Western society do at promoting each of Socrates’ themes of a just society: harmony, specialization, and virtue?

This is a line from the great Soviet dissident Alexander Solzhenitsyn: “the line between good and evil does not divide man from man but runs through every human heart.”

Very well done!