PHIL 101: Don't Worry... Be Happy

A ancient ethical system that could alleviate some of the increasing crisis of meaning in our modern world.

Aristotle is more than a generation behind Plato and was one of his students. When Plato wrote the Republic, Aristotle hadn’t even been born. The order goes Socrates (wrote nothing), Plato (wrote a bunch about Socrates), then Aristotle (wrote a bunch about everything).

To call Aristotle’s interests diverse would be an understatement: biology, physics, mathematics, logic, geometry, architecture, philosophy, art… there was basically no subject he didn’t have an opinion on. And his opinions were (mostly) so well thought out that they stood the test of time. In the 15th century, Copernicus is arguing against Aristotle. Galileo is arguing against Aristotle. Francis Bacon and Rene Descartes spend much of their careers arguing against Aristotle. This man’s ghost haunts Western intellectual life for almost 2000 years.

A Good Life is a Happy Life

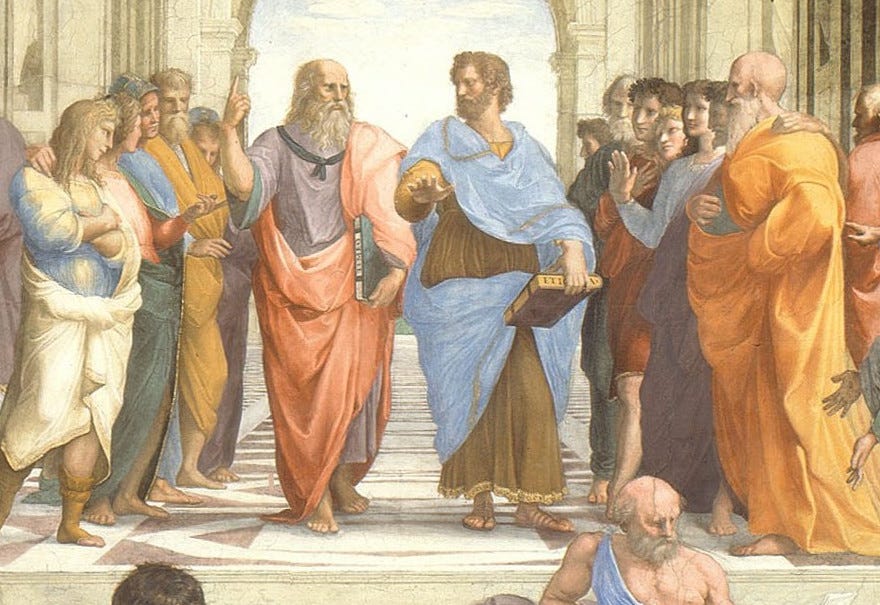

Look a those two guys at the center of the School of Athens painting by Rafael: Plato pointing upward and Aristotle with his hand flat in front of him. You can almost hear them arguing: Plato — “virtue begins with seeking the Form of Goodness”; Aristotle trying to pull his elderly tutor in a more Earthly direction — “virtue is in our actions not in the sky”. Based on their respective writings, the two men almost certainly engaged in precisely this argument, and Rafael clearly intended to convey it by the book he puts in Aristotle’s hand — Nicomachean Ethics — which is our target this week.

“Every art and every inquiry, and similarly every action and pursuit, is thought to aim at some good; and for this reason the good has rightly been declared to be that at which all things aim.” (Aristotle’s opening line of Nicomachean Ethics)

For Aristotle, the end of ethics is goodness. Not duties. Not rules. Not morals. Goodness. Aristotle uses the term eudaimonia [ef-dī-mon’-ē-a], which gets translated (poorly) as happiness. A virtuous person is one for whom behaving correctly brings happiness. While Plato is busy climbing out of his his cave to look for some abstract form of “goodness”, Aristotle thinks goodness is better learned by doing. You become a virtuous person by learning to take pleasure in consistently doing virtuous things.

That is literally the best 10 minutes I have ever seen on virtue ethics. To top it off, this guy is better than any motivational speaker. He’ll have you ready to start training for a marathon (to become virtuous of course) by 8 minutes in.

The key points:

Each virtue is always a median point between two vices. You can screw up royally in both directions.

Virtue is universal, but its application is situational. It’s a combination of doing something that “is right” and knowing when and how to do it in the correct way.

We learn virtue by emulating other virtuous people.

Becoming a good person means making virtue habitual. Our character is formed by our habits.

Aristotelian happiness (eudaimonia) is about living a fulfilled life in accordance with virtue. Happiness without virtue is as impossible as holiness without God. (Thomas Aquinas, a few weeks from now, will link these ideas explicitly.)

Each of these could be a post in itself, but this is a summary so I won’t go there. However, these points get fleshed out in the readings.

A Good Life will “Get the Goods”

I got my first shingles shot last week. I was just really looking forward to being exhausted and feverish for 24 hours and my arm aching for 3 days… of course not! I got it because my sister got shingles a couple of years ago and I want to stay healthy.1 Both shots and good health are “goods”, but they are very different. The first is a means; the second is an end. In this case, the first is a means to the second, but only a masochist looks forward to the shot itself.

Aristotle distinguishes between these types of goods:

Instrumental Goods - they lead to an intrinsic good

Shots, your job, basically anything you don’t naturally enjoy but you do for the express goal of getting something you do enjoy.

Intrinsic Goods - they bring us happiness

Useful Goods

Food, Shelter, Car - a palace or a banquet or a Ferrari are pleasurable, but for most of humanity, these are about protection and nutrition and transportation. They keep us alive and somewhat comfortable.Pleasurable Goods

Westerners are REALLY good at this category. We spend more money trying to buy pleasure (legally and otherwise) than probably any society in history.

However what’s important here is that Aristotle isn’t some kind of dour teetotaler scowling at anyone who’s having a good time. In fact, he places pleasure as one of the 3 key goals of our lives. But not as the highest goal. The highest goal is beauty.Beautiful Goods

Now this is a weird one. We think of beauty in aesthetic terms, but what does it have to do with virtue? Sometimes this word (kalon) gets translated as “noble”, which is probably closer to its meaning. A virtuous person is one who knows how to act correctly in all cases, which if you think about it, sounds a lot like the definition of nobility. But unlike nobility by birth that was common in Medieval Europe, Aristotle’s nobility is something attainable, to some degree, by everyone. (Mr. Darcy in Pride and Prejudice is admirable — and attractive to Elizabeth Bennet — because of his behavioral nobility, not that of his birth.)

Some acts are intrinsically beautiful: friendship, love, generosity are naturally ennobling to our nature as social animals. Wisdom and knowledge are noble goods for our nature as rational creatures. This is what Aristotle means by beautiful. It’s far more than aesthetic beauty, although form and proportion and elegance can be part of it. However, as Christians, we must always remember that the Evil One is described as physically beautiful while Christ is described as rather unremarkable in appearance. Don’t get too caught up in the physical aspects of beauty in this case, particularly with regard to people.

The Bads - they never lead to virtue

The beautiful cannot exist without the ugly.2 Even though his ethics is somewhat situational in its application, Aristotle marks some actions and behaviors and thoughts not just as vices but intrinsically bad. They have no redeeming qualities and always diminish man’s nobility (and happiness.) Making these into habits lowers a man to little more than an animal.

But not every action nor every passion admits of a mean: spite, shamelessness, envy; in the case of actions, adultery, theft, murder; for all of these … are themselves bad, and not the excesses or deficiencies of them. It is never possible to be right with regard to them, committing adultery with the right woman, at the right time, and in the right way, but simply to do any of them is to go wrong. (ibid)

That “stuff that’s always bad” list might look familiar. Maybe we’ll abbreviate it… sin? I am kidding, since the Christian concept of “sin” is not one Aristotle would not have recognized. It is remarkable though that a Greek, pagan philosopher writing almost 150 years before the Jewish Torah was translated outside of Hebrew would come up with a list closely mirroring the 10 Commandments. It’s almost like God had written some kind of moral law on the hearts of all men. Hmm…

The Mean - where happiness is found

For men are good in but one way, but bad in many. Virtue, then, is a state of character concerned with choice, lying in a mean, i.e. the mean relative to us, this being determined by a rational principle, and by that principle by which the man of practical wisdom would determine it. It is a mean between two vices, that which depends on excess and that which depends on defect; and again it is a mean because the vices respectively fall short of or exceed what is right in both passions and actions, while virtue both finds and chooses that which is intermediate. Hence in respect of its substance and the definition which states its essence virtue is a mean, with regard to what is best and right an extreme. (Nicomachean Ethics Book 2)

I linked a worksheet in the readings to make this “mean” concept a little more concrete.

The “mean” of virtue can only be found by testing against the vices, either by watching someone else or by making your own mistakes. Even vice is useful. While we can learn a lot from moral exemplars, virtue is “practical wisdom” and that requires making mistakes. As Will Rogers (probably apocryphally) said, “good judgment comes from experience, which comes from bad judgment.” Aristotle would probably add that the virtue of prudence is required to know when you can safely make those potential mistakes without getting killed.

Conclusion

So what is Aristotelian virtue? I like the definition given by Dr. Nathan Schlueter of Hillsdale College: “A perfected (seeking improvement) active (intentionally choosing) condition acquired by habit (performed regularly by choice) and disposing one to choose the good (good as defined in each area: sex, food, money, etc...) according to the mean (each virtue has an excess vice and a deficient vice), as determined by prudence (itself also a virtue), and to feel the correct pains and pleasures associated with that virtue (choosing the good should be pleasurable)." If you're not taking pleasure in it, you're not virtuous yet. You may have the actions, but you're still working on the state.

The focus on habituation is one Aristotle’s most important contributions to practical virtue. At an individual level, you become what you do. 90% of our choices are habit, and thank God for that since just correctly interpreting the world is hard enough for our brains. If we had to make conscious choices about every action we’d go nuts. If you actually want to improve yourself, the knowledge that most of your life runs on autopilot is great news! Want to be an organized person? Start by making your bed. Want to become a marathon runner? Go for a run every day. Want to achieve holiness? Say Liturgy of the Hours or pray the Rosary every morning. It takes about 2 months of reliable behavior to form a new habit, but once you achieve it, autopilot takes over. So hack your habits to push you toward virtue.

Thinking about beauty and virtue and happiness the way Aristotle does would benefit our increasingly theologically divided society as well. Today we talk about beauty purely in aesthetic terms, but we don't think about the moral life in terms of beauty, in terms of its intrinsic attractiveness to our will. But we all instinctively feel a calling to that kind of life. Back to Mr. Darcy — excellence of character is very appealing.

Go back and watch the last 2 minutes of the video above. Imagine living that way, always seeking something higher, training yourself for something greater, learning something new, never resting on your laurels, living intentionally and with purpose… can you really say that isn’t attractive? Could living for simple pleasure (whether football or shopping or sex or video games or romance novels or MAGA or Pride) ever compare to a life lived in that way?

That’s eudaimonia. That’s Aristotelian happiness. That’s a life worthy of a human being. In a society that agrees on little else, perhaps we can at least agree on the intrinsic value and desirability of such a life.

Readings:

Book - The Right Thing to Do (Chapter 4 - Aristotle’s Virtues)

Nicomachean Ethics (selections)

Applying Aristotle to Modern Ethical Dilemmas (BBC)

Virtues and Vices Worksheet (the second page has my answers)

Review Questions:

What goods or actions are intrinsically good to themselves, or are simply means to other goods?

How is happiness a function of virtue? Why is an un-virtuous person is incapable of happiness? (Hint: Book 10, Ch 6)

How does Aristotle’s definition of happiness compare with the modern world’s “if it feels good, do it”?

“Even a slave can enjoy the bodily pleasures, but no one assigns to a slave a share in happiness” (Book 10, Ch 6)

Thinking of how Aristotle views character as formed by habit, do you think this is a dig on the innate character of slaves or on the effects of being enslaved on a man’s character? Is it fixable?Compare Aristotle’s the last paragraph of Bk 10, Ch 8 with 1 Corithians 13.

Aristotle says he who cultivates reason is nearer to the gods.

Saint Paul implores Christians to “put away childish things”.

What differences and similarities do you see between these sentiments? Can you unify them? In a few posts you’ll see how Thomas Aquinas attempted to.

Seriously, if you are over 50 and haven’t gotten a shingles shot, don’t wait. Shingles can be months of painful misery.

There’s a wonderful short story by quasi-sci-fi author Ted Chiang called Liking What You See that plays with the relationship between beauty and ugliness in a fascinating way. It’s part of a short story collection that also includes the story the movie Arrival was based on. Chiang incorporates religious themes and people like no one since Heinlein or Phillip K Dick. A great summer read.