PHIL 101: The Rediscovery of Reason

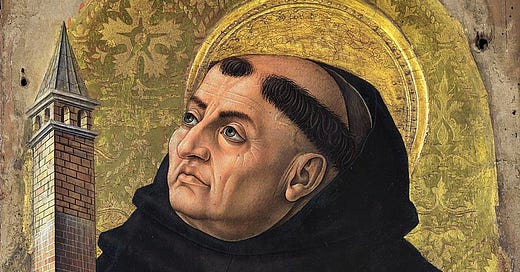

When Greek philosophy was reintroduced in the West, a monk named Thomas Aquinas set out to square Aristotle's pagan theories of virtue with Catholicism.

In the last 3000 years, 2 events stand out for the level of destruction they wrought upon civilization in Western Europe. The Medieval Black Death gets all the press, but its impact was negated within a century. These two still echo today:

Burning of the Library of Alexandria - Julius Caesar inflicted this intellectual tragedy (accidently according to Plutarch) while putting down a rebellion. It destroyed scrolls going back to the earliest days of writing.

The Sack of Rome - Catastrophic in a more practical sense, the population of Rome was cut by 80%+. So many people were killed and so much skill-knowledge eliminated so quickly it set Western Europeans back 500 years in the blink of an eye.

Within 3 generations, those still living in Western Europe were surrounded by buildings that might as well have been dropped by gods, since no one alive could recreate them. The Pantheon in Rome (built AD 126) remained the largest cast concrete structure in the world until Hoover Dam. Materials scientists are still teasing out the secrets of ancient Roman concrete’s strength.1 No, it wasn’t a “Dark Age”, but it was along slog just to restore the quality of life that had been lost.

Fast forward 700 years, and Europe is finally getting back on track. A church being remodeled outside Paris is incorporating a new style of architecture ironically called Gothic.2

Aristotle Rediscovered

And it’s not just buildings. Christian Europe is digging up writings from ancient Greece and Rome: Euclid, Ptolemy, Plato, and Aristotle, who’s ideas returned to Western Europe via Arabic translations. When Muslims invaded Spain from North Africa (11th-12th century), Toledo became a major locus of intellectual cross-pollination between Muslims, Christians and Jews. Plato and Aristotle are re-translated into Latin here, and their ideas work their way throughout Catholic Europe via the monastery education system.

A young Dominican novice named Thomas Aquinas first encounters Aristotle via one of these translations in his native Sicily. Aquinas is impressed with Aristotle; his abbot is impressed with Aquinas; and several years later, now friar Aquinas travels to study at the University of Paris, where he enters the tutelage of Albert of Cologne (aka Saint Albert the Great). Albert is enamored with the ancient Greeks and Romans and has newer translations taken directly from Greek manuscripts. Like any grad student would be, Thomas is thrilled to get early access to an Aristotle not polluted by Islamic philosophy.

He joins a group of Paris scholars known as the Scholastics who seek to harmonize neo-Platonic and Aristotelian philosophy with Catholic theology. This union, and this monk, will come to define the future of Western Civilization. The sorts of questions the Scholastics were asking:

Can human Reason prove the existence of God?

How much of God can be understood with human Reason?

What is the boundary of Reason and Faith?

Is human language an appropriate vehicle to describe God?

How can divine providence be squared with free will?

Does using Reason to analyze the world diminish Faith?

Can Reason and Revelation ever contradict each other?

If you think the answers to these questions are obvious, it’s only because the work of Aquinas and the Scholastics has so permeated Western Christian philosophy that you don’t even realize it’s there.

Let’s just look at the first question on this list:

The echoes of Plato and Aristotle here should be obvious. We’ll look at Aquinas further’ works on natural law and virtue in the next few posts.

Influenced by Aristotle’s Prime Mover, Islamic scholars had already come up with a similar idea (the Kalam Cosmological argument). I do wonder if Aquinas’ early Arabic translations tacitly incorporated these Islamic theories into Aristotle, giving the monk a jumping off point for his own studies.

The impact of Aristotle’s Prime Mover reasoning and Aquinas “logical proofs of God” can not be understated, especially for Protestants. We Protestants have a deep faith in the use of language to describe God — sola scriptura! — and generally expect Him to be reasonable and accessible. Medieval man expected the world to be random and illogical: a plague could kill you; the local noble could evict you; the future was unpredictable. Creation was capricious, so why should God (the author of Creation) be reasonable? Thomas Aquinas changed that for Western theology, and Francis Bacon (who we’ll get to someday) changed it for Western science.

Aquinas Style

The title Summa Theologiae, the book Aquinas is most famous for, literally translates as “Complete Theology”. Your pastor’s bookshelf full of titles that start with “Systemic Theology of…” (whether Ockham, Calvin, Arminius, Wesley or John McArthur) are echoes. Despite its comprehensive nature and huge scale though, the Summa is a very easy read. Each chapter takes this form:

Article - a question being asked (“Is God’s existence self-evident?”)

Objections 1, 2, 3… - arguments against the hypothesis

(No strawmen; Aquinas nearly always presents the best objections.)On the contrary - a citation from authority against the objections

(Saint Paul is “the Apostle” and Aristotle is “the Philosopher”.

Aquinas held both of these men in very high regard.)But I say - Aquinas’ answer to the question

Reply 1, 2, 3… - Detailed rebuttal of each objection

Even for us moderns (saying nothing of the theological content) Aquinas is a profound lesson on how to organize your thoughts and effectively communicate them. Would that our political leaders read Aquinas if only for this reason.

The reading below is Question 2: On The Existence of God. These 3 articles give a great introduction to Aquinas’ format and cover the same critical question as above: is it reasonable to conclude that God exists? Aquinas’ answers even in the first few pages reveal much of his thinking, ideas which remain largely unchanged in Catholic and especially Protestant circles even today.

It’s amazing that Article 3 — Does God exist? — was written 800 years ago. The objections raised sound so modern: the existence of evil and the self-sufficiency of nature. These remain the most common objections to God’s existence even today. C.S. Lewis’ Problem of Pain is a Protestant answer to the the existence of evil, but owes a deep debt to the Summa. (Unlike most Protestants, Lewis knew it.)

Most of the Church Never Lost Aristotle

Aquinas wasn’t the first theologian to attempt to unify Athenian philosophy and Christian revelation — just the first Roman Catholic. Unlike Western Europe, the Eastern Church didn’t have a Dark Age. Rome collapsed, but the Roman Empire continued as a Greek/Christian empire in Constantinople.

They spoke Greek (see the captions above) and Aristotle was a standard feature of Byzantine education. Aquinas didn’t realize the questions he was wrestling with had been answered centuries earlier. But the Eastern answers were slightly different.

The Orthodox / Byzantines incorporated neo-Platonic ideas gradually and organically, having retained the original philosophers’ skepticism of the limits of human reason — Plato’s famous heart as the governor between emotion and reason is a good example. The East took pagan philosophy as a long slow meal, tasting here and there, savoring the best dishes, and deciding slowly what was agreeable and what should be discarded.

The West’s encounter with Greek philosophy was far more sudden, and they approached it like a starving man tossed into a buffet. Lacking the centuries of study, they completely missed the finer flavors like the ancients’ skepticism of human reason and instead gulped down everything. They didn’t take the time to digest, and ended up with a stomach ache that persists (as part of the Great Schism) to this day.

This is the core difference between Eastern and Western treatments of Aristotle, and a huge part of the reason Eastern Orthodoxy feels so foreign to us. The question above — “Is human language an appropriate vehicle to describe God?” — is answered very differently between West and East. And from the Eastern perspective, Catholic and Protestant answers look pretty similar. I’m not going further into Orthodox philosophy (I’m not qualified) but I do encourage Protestants who are disaffected by the strict rationalistic approach to God to explore Eastern answers. I just wrote a review of the best book I’ve found for that.

Aquinas End

A few months before he died, Aquinas had a vision. Alban Butler’s Lives of the Saints describes it this way:

On the feast of St. Nicholas [Dec 6th in 1273], Aquinas was celebrating Mass when he received a revelation that so affected him that he wrote and dictated no more, leaving his great work the Summa Theologiae unfinished. To Brother Reginald’s (his secretary and friend) expostulations he replied, “The end of my labors has come. All that I have written appears to be as so much straw after the things that have been revealed to me.” When later asked by Reginald to return to writing, Aquinas said, “I can write no more. I have seen things that make my writings like straw.”3

What did Aquinas see? If he told Brother Reginald, the younger monk never revealed it. But I wonder if he got a vision of Heaven that shifted his outlook to be more Eastern. Did he call his writings “like straw” since he was now more skeptical of reason’s ability to accurate perceive God? I don’t know. No one does. Because he died 3 months later.

Readings

Wisdom 13

(Luther scrapped the book from our Bible, but Aquinas used it.)

Saint Anselm’s Ontological Argument for God

(Aquinas is responding to Anselm in Objection #2 of the first question.)

For anyone who wants a very accessible version of the Summa, I recommend Peter Kreeft’s Shorter Summa.

Just for fun, and to understand Aquinas personality better…

Questions

Summarize Anselm’s Ontological Argument for the existence of God. Why does Aquinas disbelieve Anselm?

If you remember, Saint Augustine was very focused on Romans 1:20.

Read Aquinas’ Summa Article 2, On the Contrary and Reply to Objection 2. Aquinas uses the same verse. What is his focus on this verse? Give some examples of how he or Augustine might “understand God through the things that are made”.If God is omnipotent, can God create a triangle whose angles don't add up to 180 degrees? If not, doesn't that make him non-omnipotent? (You won’t find the answer in the readings; can you prove something the same way Aquinas does?)

Read through the 2 objections in Article 3. To this day, these remain the dominant objections to Christianity’s veracity. Summarize each of them in your own words and Aquinas’ response to each.

Which of Aquinas “5 Proofs of God” do you find the most convincing?

William Craig’s video above uses Aquinas’ logic to alter Aristotle’s Prime Mover hypothesis in an important way. What additional attribute does he believe can be demonstrated beyond Aristotle?

Our roadways and sidewalks decay after 50-100 years. Yet the Pantheon is still standing after 1900 years. We could not do that today even with rebar, which the Romans didn’t have.

The new style of building featured pointed arches instead of round, ribbed vaults instead of thick walls, large stained glass, and lots of sculptures and gargoyles. Like any new trend, some hated it and took to disparaging it as Gothic, an insult taken from the Goths, the tribe that finally sacked ancient Rome.

Taken from catholic.com.

That Aquinas was from Sicily and first encountered Aristotle there was a revelation to me.

For no very profound reason I vacationed ther not long ago and it was a relvlation of the importance Sicily has been in history Syracuse, Epirus, First Punic War, the Normans, Garibaldi